The following story was originally printed in the

Kansas City Star. Since it's been removed from their site, I'm reprinting it here.

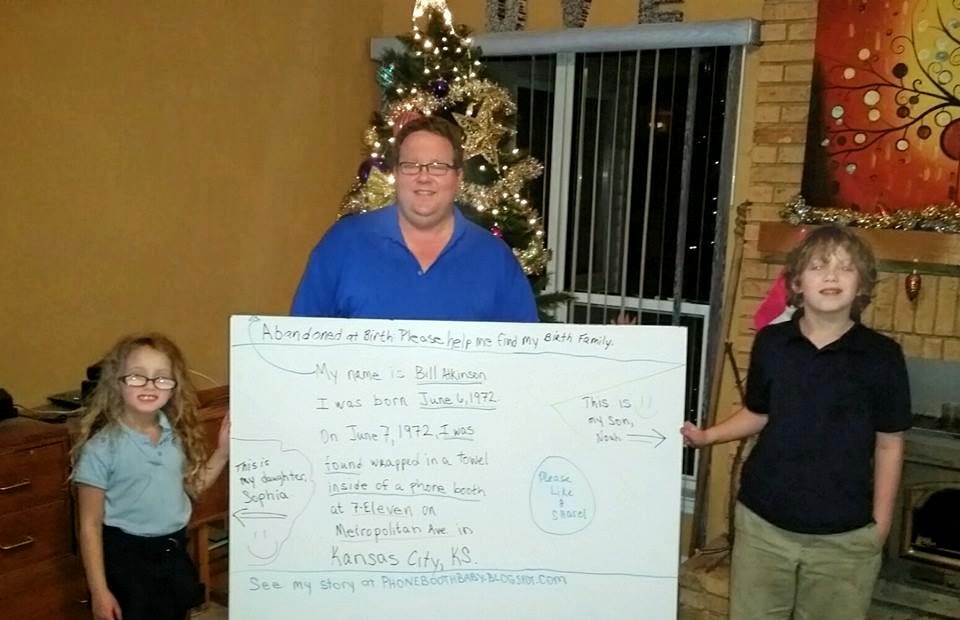

Everyone calls him Bill Atkinson. Before that, he was Stephen Michael Doe. And before that, well, that’s the mystery.

He was found, abandoned, in a phone booth, less than a day old and covered in nothing but a blanket. The puzzle of his origins remains unsolved a generation later.

Now a 41-year-old husband and father of three, he’s hunting for the family he never knew — the woman he never got to call Mom, the man he never called Dad.

But where to start?

Short articles in The Star and The

Kansas City Times offer only tenuous clues of that

June 7,

1972, morning. He was discovered bawling by a woman at a 7-Eleven store at 4039 Metropolitan Ave. in

Kansas City, Kan. Doctors figured he was just 12 hours old at the time. One story said he weighed 5 pounds 8 ounces, another had him at 6 and a half pounds.

He has no interest in replacing the only family he’s ever known, whom he loves as much as ever. But now that he’s started his own family, he wants answers that might give his children valuable information about medical histories — and his distinct personal history.

“I want to know more,” Atkinson said, about “people who look like me, who think like me and other family that are like me.”

He and his wife, Angie — in fact, it’s largely her crusade — have been searching for nearly a decade.

A youth bureau detective who arrived at the scene is dead. So is the doctor who cared for him in the hospital. And the woman at

Wyandotte County Social Services responsible for finding him an adoptive

family offers no clues.

“It’s crazy that I can’t remember,” said retired social worker Linda Hobbs. “My memory is usually a steel trap.”

Every link in the chain that might have led to answering questions about his past has been broken.

The trail begins and ends with a phone booth that no longer exists.

Yet the search goes on.

“It would help him to have some understanding” his wife said. “There’s a piece of him that needs to know. … For that reason, I will never stop.”

Laura Long, a search specialist for Adoption Search Services, said most people searching for biological parents can use the court system to unearth their heritage.

In

Missouri, adoptees can ask a court for identifying information if they have the

birth parent’s consent or if the

birth parent is deceased. That information would be the name of the

birth parent, a

birth date or anything else that would help adoptees identify their

birth parent.

Sometimes a court will allow a third party to contact a birth parent to seek his or her consent.

Lacking proof of death or consent from the birth parent, only nonidentifying information is available. That leaves age, occupation, whether the parent had siblings — only information that would not give away the identity of the birth parent. But record-keeping can sometimes be spotty.

Long, a Kansas City native, was also adopted. Almost 15 years ago, she reunited with her birth family and she’s devoted her career to helping others do the same.

“These are people meeting for the first time, so it’s like anyone meeting for the first time,” Long said. “They might never see each other again, they might exchange Christmas cards once a year and they might even become best friends, you just never know.”

Long’s business works with courts to help people find their birth parents.

“You’d be amazed how many years it takes and how much money people will spend looking on their own,” Long said.

She told a story of a woman who searched for 14 years, refusing to involve authorities because friends urged her not to use the court system.

“She eventually gave in, went to the courts and within two weeks we had the birth mother contacted,” Long said.

The courts are a key to opening records. But for Atkinson, there are no revealing records to unlock.

He has a birth certificate, but the only name on it is Stephen Michael Doe — the name given to him when he was found.

As a child, his adoptive father wanted him to succeed at sports, even hiring a swimming coach to get him ready for the Junior Olympics. But his dad died when Atkinson was 12, and that dream faded away even as he swam competitively and played soccer at a Catholic grade school in Blue Springs.

Atkinson was raised by parents who made clear he was “the greatest thing that ever happened” to them.

“They brought me up as good, if not better,” he said, “than anyone else could.”

Atkinson’s father was a salesman who traveled frequently. That left Atkinson and his stay-at-home mother, Patricia, on their own. He remembers being spoiled, buried in presents at Christmas whether his father was home or away.

After his father died, Atkinson’s mother told him he was adopted.

“I didn’t believe her at first,” he said, “so she had to show me the KC Star article.”

Now, as an adult, he works in information technology. He’s raising his family in suburban St. Louis.

Naturally, he still loves his mother and talks to her regularly.

The need for answers about his biological mother came only when Bill and Angie Atkinson had their first child together — Noah, who is now 9. He knew how much his mother must have loved him, even if she could not raise him.

The Atkinsons’ search has lead them to many dead ends. But last year, they thought they had a break.

Angie Atkinson found a family through an adoption website. She made contact with a woman who was potentially Bill Atkinson’s niece. That woman was looking for a boy born about the same time as Bill.

It was the wrong family. The baby they were looking for was born in 1970, not 1972.

“They looked so similar and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, there’s no way,’” Angie Atkinson said. “I really thought that might be his family, and I’m still not sure it’s not, but apparently it doesn’t matter.”

She concedes some wishful thinking. Because the years don’t match, it certainly can’t be the same boy. But the family sent them pictures and the resemblance was uncanny. Atkinson has blond hair and blue eyes and stands 5 feet 10 inches tall.

“I did get a little bit nervous, but also excited,” Atkinson said at the thought of possibly meeting his birth family. “Angie had asked me, ‘Are you willing to drive out there and meet them if this is it?’ … At that point, I definitely was.”

Yet, there’s a fear of what they might find. His biological family might not want to be found. They might not want to know him. They might be dead.

“It would be tough not to get an answer. It would be tougher if they were dead,” he said. “They wouldn’t have a chance to tell me … maybe they wanted to find me. Maybe they’re ashamed of what they did.”

Still, he wants to unravel the mystery of his beginning and his abandonment, to be able to ask somebody where he came from.

“I feel,” he said, “like I deserve an answer.”

.jpg)